How video games were used as a social currency for a bunch of military brats growing up in Germany.

Thanks to accidents of birth, geography, and not owning a boat, getting video games at all – let alone playing the bastards – was hard when I was a kid in a military family. While there were many advantages to not living in Britain in the 90s – mainly that you weren’t living in Britain, and as such missed Britpop, ill-founded faith in politics, and a slew of other terrible things – there were, if you loved video games, a whole host of disadvantages. Those disadvantages multiplied if you lived in a country like Germany, which famously doesn’t get along with the games about the blood and the killing. Back then, even more so than now, that category appeared to include every single game ever made. Which wasn’t great if you were 11, and all the games you wanted featured The Blood and The Killing.

Granted, it was difficult for all kids to get ahold of games at that particular time, what with the absence of money coupled with massive cartridge prices . But living abroad brought its own set of specific challenges: languages; availability; compatibility; replayability. There was no trading games back in at the local Hypermarkt. Renting was not an option, either: Nintendo was still at war with that particular business, and besides, nowhere near me had cottoned onto the fact that there was massive money to be made from rabid kids and tired parents.

Children being the industrious and devious little bastards they are, however, I soon found myself in an ad-hoc club of sorts, where access was key and whoever had the goods was the most powerful person in the town of Hameln, the Pied Piper having long since been usurped by my friend Daley and his copy of Earthworm Jim.

Ours was an odd world, even if it seemed perfectly natural at the time. The constant influx of new arrivals as people’s parents were posted in and out of the local military presence meant that the market, as it were, always saw fresh (and, sometimes, rare) ‘stock’ flow in. Trading games between friends isn’t new or novel, but when just getting the games at all seems like a logistical nightmare, there was a special premium associated with them when they arrived.

Having grandparents willing to set up a ‘supply route’ and send you games from Britain made you a mini-Escobar.

Take Paul, for example, and his elder brother Richard. Now, older siblings were almost as useful as the aforementioned grandparents: they were less likely to send you something bad, and were perfect foil for nefarious plans. “Yes, mum, I’ll make sure they don’t play Mortal Kombat. No mum, they’ll be in bed and not watching Alien on Sky Movies Gold.”

But while Richard had his uses, it was his dad who had something truly rare: a proper, honest-to-goodness gaming PC. Maybe even a 486. Word soon spread that the boys not only had Wolfenstein 3D, but also Doom (which made you the most important person in the world at that point, save maybe Eric Cantona), and some weird thing called Rise of the Triad. Paul and Richard always claimed that we couldn’t come over to play it because their dad never wanted anyone in the house, which now strikes me as perhaps a massaging of the truth, but then such are the levers of power. The closest I got to seeing Doom moving at its thunderous, impossible speed was when I glimpsed it as Paul left to come out and play football. Having only seen it in stills in magazines, it was a revelation. And then the front door closed and it was gone, like an alternate Godfather ending 30 times more tragic than the one we actually got.

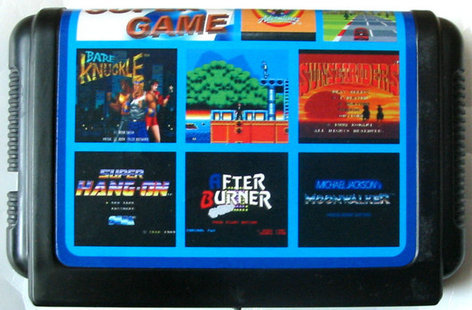

Other items caused huge commotions in the playground. News of a Mega Drive version of Super Street Fighter II arriving in town demanded an immediate investigation, which ended when a beleaguered schoolfriend was press-ganged into providing the cart as proof. (He had previously shown us the manual, evidence that was considered circumstantial at best.) Another new arrival was forced into a school assembly show and tell, where the teachers cooed over the fact he’d been posted from ‘exotic’ Asia. Of more interest to almost everyone else was his Mega Drive variant, and the fact he had games with more than one title on a cart, familiar to most as the ‘Lanzarote Special’.

Everyone had a story like this, and in retrospect it was obvious why. The life of a military brat is a transient one, especially if you’re based somewhere other than Britain. Every single person you met was on borrowed time: who knew when they’d be leaving for another town, another school, another round of trying to integrate themselves into a social hierarchy. Once you left, that was it: for all intents and purposes your old buddies were gone forever, defined in hindsight by what games you played with them.