How CD Projekt Red added Polish to every detail of the game world.

Revisiting familiar media is a natural reaction to troubled times. Given that we’re in the middle of an international pandemic, it’s fairly safe to say that times are, indeed, troubled. Many of us turned to Star Wars, Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter as surely as we turned to banana bread and Tiger King. While my friends were re-reading Twilight, I spent my home-bound weeks replaying The Witcher 3 for the eleventh time.

To say The Witcher is familiar to me is a bit of an understatement: I read Sapkowski religiously as a kid and was absolutely astounded when the first game was announced. Seeing Geralt in a 3D on my screen was a dream come true (my other dream was to see him in 3D IRL, that did not come true yet). To emphasise how much of a nerd I was, I’m going to confess I came second in a local The Witcher writing competition when I was 16. The main prize was The Witcher 2, but all I got was a Geralt-themed Razer mouse mat that I was too ashamed to claim.

So, after finishing the game (and getting the same ending for the eleventh time), I decided to use my Witcher expertise for good. I’m here to help those of you who may have missed the Slavic undertones in your favourite quests. All three games are ripe in references to Eastern European culture, from lines that NPCs yell at you as you pass them to entire questlines. Hopefully, I’ll be able to shine a light on the hidden meaning behind the world, the quests, the characters and the monsters of The Witcher 3. I bet it’ll make you appreciate CD Projekt Red even more!

Spoilers ahead.

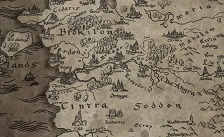

The world

The world of The Witcher 3 is heavily influenced by Slavic folk. It doesn’t shy away from established fantasy optics, but it has its own, distinct visual language. The result was a familiar-yet-novel experience for audiences outside of Poland.

From thatched huts, whitened with lime or chalk, to decorated dowry chests, the Northern realms are full of references to Slavic culture.

If you ever dreamt of transporting yourself to Velen (sans monsters, of course), Lublin Open Air Village Museum is where you need to go. You can even get that Witcher rush of adrenaline if you come too close to one of the feisty goats that roam the Museum freely.

Colourful, decorated huts of White Orchard and Velen are directly inspired by the village of Zalipie in southern Poland, just a 90-minute drive from Kraków.

The folk decoration of Pająki — colourful hanging ornaments made of blotted paper and straw —are immediately visible at the White Orchard Inn at the very beginning of the game.

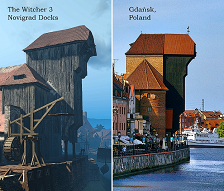

The free city of Novigrad takes inspiration from the formerly-free city of Gdańsk, with devs going as far as including a model of its famous crane. Just like Gdańsk, Novigrad is a bustling trade city and an important international port. Gdańsk’s architecture stands out amongst Polish cities, and there’s a clear parallel between Gdańsk and Novigrad both layout and architecture-wise.

The cursed tower on Fyke Island is also a real place (though far less cursed IRL). Called Mysia Wieża (Mice Tower), it’s tied to a folk story related to a 9th-century proto-Polish ruler named Popiel. As the legend goes, the greedy king Popiel’s corruption and misrule led to a rebellion. As he locked himself in the tower, a host of mice scurried in and ate him alive.

Similarly, in The Witcher, we find out the former inhabitant of the tower, a selfish nobleman, refused to share food with his subjects, who in turn stormed the tower and murdered everyone inside. His daughter, left in a magical slumber by a mage, was eaten by rats.

The landscapes of The Witcher are heavily influenced by Poland, too. From Teutonic Order-inspired ruins scattered across Velen and White Orchard, through towering mountains and flat pastures, to hollyhocks adorning villages.

The quests

Czeslaw Borys Jankowski.

The aforementioned Fyke Island hosts another quest that heavily borrows from Polish legends and literature. At some point, a character named Pellar (Guślarz) will ask you to assist him in an ancient ritual called Forefather’s Eve (or Dziady). Dziady is a Slavic feast commemorating the dead. It’s also the title of Adam Mickiewicz’s epic poem that’s considered to be one of the masterpieces of European romanticism.

Similarily to the Forefather’s Eve quest, the plot of Mickiewicz’s masterpiece centres around ghosts being summoned from beyond the grave by the villagers to help them reach salvation.

Bald Mountain is not only the site of a quest based on a Polish folk story but also a real place (sans the cool tree). Bald Mountain was actually an ancient Pagan cult site, where Slavs held Dziady feast regularly and where Polish witches gathered on Midsummer (in Poland known as Kupala Night).

The main storyline of Heart of Stone is inspired by the Polish legend of Pan Twardowski, a nobleman who sold his soul to the devil in exchange for magical powers, with the intent of never fulfilling his end of the bargain. Using a magic mirror he got from the devil, Twardowski summoned the deceased wife of King Sigismund Augustus. Due to a clause in the contract between the devil and Twardowski, the latter was supposed to give up his soul in Rome which he planned to never visit — but was outwitted by the devil who took his soul in an inn named “Rome”.

While Heart of Stone is heavily influenced by the legend of Pan Twardowski, the character of Olgierd von Everec is closely tied to Kmicic from Henryk Sienkiewicz’s novel The Deluge (Potop). Just like Olgierd, Kmicic is a rowdy nobleman who becomes increasingly likeable over the course of the story.

One of the side-quests of Heart of Stone takes you and Geralt’s friend Shani to a village called Bronovitz for a wedding. Bronovitz (Bronowice) is also the setting of The Wedding, a play by Stanisław Wyspiański. The play itself was inspired by a real wedding that Wyspiański himself attended. Bronowice is now one of 18 districts of Kraków.

The monsters and the characters

The word “witcher” (“wiedźmin”) itself comes from “vedmak” (“wiedźmak”), which literally means a male witch and was mostly used as an insult. The profession of a witcher, however, is Sapkowski’s original concept.

Multiple creatures of The Witcher series are inspired by Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon mythology (amongst many others), however many are taken directly from the Slavic pantheon.

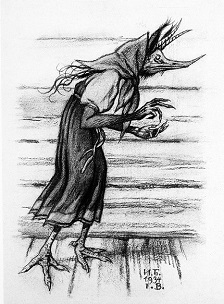

Noonwraith (or Południca) was believed to be a spectre of a woman dressed in white that roams fields around midday, kidnaps children and causes madness. She was meant to cause bouts of confusion, neck aches and dizziness, which all match the symptoms of heatstroke.

One of the toughest in-game enemies, Leshy (Leszy or Borowy), is also one of the best-known Slavic deities. Humanoid and masculine, he was to guard forests and swamps. Even though some believed Leshy to be evil, in most cases he was thought to behave towards humans as humans behaved towards nature. He could have led travellers astray as much as guide them safely out of the forest.

Some believed Leshy to be married to Kikimora of the swamp — however, the Kikimora of the Witcher world differs significantly from Pagan beliefs. Kikimora was an evil presence that woke newborns up at night and harmed domesticated animals, but she was also considered to be the sleep paralysis demon of Slavic people. She was portrayed as an old, small, thin woman, which contrasts with the portrayal of Kikimoras as spider-like monsters in The Witcher series.

Godlings (ubożęta or bożęta) were, unlike the Kikimora, considered to be a positive household presence. Godlings were protective sprits that brought luck and prosperity in exchange for leftovers, gifted to them on Thursdays. They weren’t, however, seen as children like Johnny and Sara from The Witcher 3 — more often, Godlings were portrayed as small bearded men.

There are many other creatures, characters and monsters inspired by Slavic culture and mythology in The Witcher games, enough to fill a book (or at least a couple of articles). The merger of the fantasy cliches like ghouls and vampires with Slavic beliefs is what makes the world so enticing to fans worldwide. Eastern European folk stories are familiar enough to be palatable to the mainstream gaming audience while remaining distinct. CD Projekt Red have done a brilliant job translating these cultural differences into a cohesive work of art.

With Cyberpunk 2077 coming soon-ish, I’m excited to discover references the Polish CDPR devs surely hid in the game. Watching the recently released gameplay footage I already spotted a nod to a long-standing Polish meme and I hereby promise to cover it (and, inevitably, many others) after the release of the game.